- Home

- Susie Finkbeiner

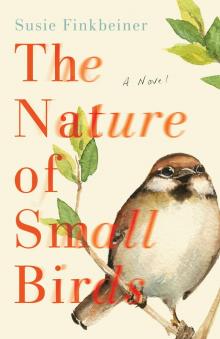

The Nature of Small Birds

The Nature of Small Birds Read online

Books by Susie Finkbeiner

All Manner of Things

Stories That Bind Us

The Nature of Small Birds

© 2021 by Susie Finkbeiner

Published by Revell

a division of Baker Publishing Group

PO Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287

www.revellbooks.com

Ebook edition created 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

ISBN 978-1-4934-3046-8

“The Language of the Birds” by Amy Nemecek was first published in The Windhover 25.1 (February 2021) and is used by permission of the poet.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

For

Elise Marie,

Austin Thomas,

and Tim Spence.

My three small birds.

Contents

Cover

Half Title Page

Books by Susie Finkbeiner

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

About the Author

Back Ads

Back Cover

The Language of the Birds

On the fifth day, your calloused fingers

stretched out and plucked a single reed

from the river that flowed out of Eden,

trimmed its hollow shaft to length and

whittled one end to a precise vee

that you dipped in the inkwell of ocean.

Touching pulpy nib to papyrus sky,

you brushed a single hieroglyph—

feathered the vertical downstroke

flourished with serif of pinions,

a perpendicular crossbar lifting

weightless bones from left to right.

Tucking the stylus behind your ear,

you blew across the wet silhouette,

dried a raven’s wings against the static,

and spoke aloud the symbol’s sounds:

“Fly!”

AMY NEMECEK

CHAPTER

One

Bruce, 2013

No matter how the world has changed over the course of my life, somehow crayons still smell the way they did when I was a kid. A fresh pack of Crayolas sits open on the kitchen table, and I roll the one called “Macaroni and Cheese” between thumb and finger.

My youngest granddaughter sits next to me, coloring heart shapes and smiley faces all over her piece of printer paper. We’re busy making cards for her great-grammy—my mother—whose birthday is over the weekend. So far Evie’s got more wax on the page than I do.

“How old is Great-Grammy gonna be?” Evie asks, switching to a light shade of brown.

“Eighty-five,” I say.

She looks up from her coloring to give me a drop-jawed look. “That’s really old.”

“Well, let’s not say that to her, all right?” I give her a wink.

Evie gives me a thumbs-up before going back to her work.

Boy, do I love spending time with this girl.

“You’re doing a good job,” I say, tilting my head to look at her picture.

“Thanks,” she says. “Do you think Great-Grammy will like it?”

“Of course she will.”

A gust comes in through the open window, making the corner of Evie’s paper flicker just a little bit. Outside, the tops of the trees sway and the leaves that have already fallen to the ground ride the wind across the yard.

Man, do I love fall in Michigan.

I fit my crayon back in its place between the deep orange and goldenrod yellow. “You know what. I’m getting thirsty.”

“Me too,” she says, letting her shoulders slump as if she’s been laboring over that card all day.

“How about I make us some hot cocoa?” I narrow my eyes at her. “Would that be all right with you?”

That gets her to perk up right away, and she tells me, “Yes, please.”

As soon as the weather drops below sixty degrees, Linda makes sure we’re well stocked with the fixings for hot cocoa. The mix, marshmallows, the works. Our oldest, Sonny, likes to point out that it wasn’t this way when she was a little girl. I like to remind her that we weren’t grandparents then.

I hardly get the cupboard open to pick two mugs before I hear a thunk on the window. A quick look and I see a little sparrow, unmoving, on the grass, wings splayed on either side. Its head is turned at a funny angle.

“What was that?” Evie asks, eyebrows scrunched together.

“You stay right there,” I say by way of answering. “I’ll go check it out.”

I rush to the family room and push open the sliding door, stepping out onto the patio.

The late morning has a hint of chill to it as if to remind me that winter isn’t as far away as I might like to think. I wish I’d slipped on a pair of shoes. Socked feet aren’t always the surest, especially on leaf-covered grass. Last thing I need is to fall, especially while I’m supposed to be taking care of Evie. At my age—sixty-ahem years old—it’s not so easy to recover from a tumble.

Trying my best not to startle the bird—a house sparrow—I lower myself, pressing one knee into the ground, hoping to see a sign of life.

“Grandpa?” Evie’s on the other side of the window, fingers curled and pressed against her cheeks. “Is it dead?”

“I don’t think so, honey,” I say, smiling at her. “How about you see if Grandma has a dry washcloth in the drawer. All right?”

She nods, but the look in her eyes says she’s feeling more than a little bit worried. I’m more than a little relieved when I notice the slight rise and fall of the sparrow’s chest. She’s breathing. That’s something at least. By the time Evie comes out, cloth in hand, the sparrow’s managed to get herself sitting up.

“She’ll be fine in a few minutes,” I say, as calm and gentle as I can so as not to startle the bird.

I use the washcloth to pick up the sparrow. She rests in my cupped hands, and I resist the temptation to run the tip of a finger over her feathers. They look like they’d be soft to the touch.

But birds like this one are wild, not meant for the affections of humans. Instead, I just watc

h her, hoping she recovers from the shock she’s had this morning.

“‘There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow,’” I whisper after a minute.

“What’s that mean?” Evie asks.

“Well, it’s from a play called Hamlet,” I say, noticing how the sparrow blinks at the sound of my voice. “It just means that God sees everything and cares, even if it’s just a little critter smacking into a window.”

Evie doesn’t take her eyes off the bird and doesn’t give me any indication that she understands. That’s all right. Sometimes I have a tough time comprehending it too.

The sparrow gives a little tremble, and I make a shushing sound like the one I always made when comforting one of my girls when they fell off their bikes or stubbed a toe.

“That’s it,” I say when she tries her wings, stretching them with a little twitch. Keeping them spread, she gives a tiny, tentative hop.

Then a second hop with a bit more certainty.

“Can we keep her?” Evie asks, putting a hand on my shoulder.

“I’m afraid not, honey.” I shake my head. “She wouldn’t like being a pet, I don’t think. She needs to be free.”

I flatten my hands, hoping to give the sparrow a better surface to take off from. She’s hardly an ounce; I barely notice the weight of her at all. But when she pushes off to fly, saying goodbye with a little trill, I miss how she felt in my hands.

We watch her go, Evie and me, until we lose her in the branches of the ancient sycamore at the far end of the yard.

My sweet girl lowers her head to my shoulder, and her sniffles let me know that she’s crying. Well, I feel like crying too, just for a different reason.

“I wanted to keep her,” she says.

“I kind of did too,” I say. “But it wouldn’t have been good for her.”

“Will we ever see her again?”

“I bet we will, sweetheart.” I put my arm around her and kiss the top of her head.

I look back toward the spot where I last saw that bird, not saying that house sparrows are a dime a dozen, if that.

Still, it’s something to see them fly.

Linda’s car is in the garage when I get home from dropping off Evie and running a few errands. When I come inside the house, I hear her singing along to the radio in the kitchen. Her voice is a deep, satiny ribbon of alto that I could listen to all day long. It’s an old Carpenters tune, and her tone is every bit as smooth as Karen’s was.

She perks up, ending her song, when she sees me. I wish she’d just keep on singing, but it would only embarrass her if I said so.

Years ago, before she met me, she’d had dreams of playing alongside the likes of Dusty Springfield and Janis Joplin. It isn’t lost on me that she chose to settle down and start a family with yours truly instead of heading out for the San Francisco music scene.

I admit that I’m biased as the day is long, but she could have made it out there.

“Hey there,” she says, rolling a ball of ground beef between the palms of her hands. “Did you have a nice day with Ev?”

“I did,” I answer. “We rescued a stunned bird.”

“How about that?” She drops the meatball into the pan. “Did she want to keep it?”

“Yup. But she understood when I said we couldn’t.”

“She’s a sweet girl,” she says. “You don’t mind meatballs for supper, do you?”

“Nope,” I say.

“Good. I wouldn’t want you going hungry.” She winks at me before pinching another hunk of ground beef and rolling it.

“Mindy eating with us?”

“As far as I know.”

Our middle daughter’s been back home for a couple of weeks—temporarily, of course—and we’re still figuring it all out. We’re doing our best to have an abundance of grace for her right now. It’s got to be tough to be forty-two and starting all over again.

As far as grace goes, I’m happy to extend it to Mindy. That husband—soon to be ex—of hers, however, is a different matter altogether.

I clear my throat, trying to convince myself to forgive anyway.

Man alive, it’s hard.

Harder still for Mindy, I have to imagine.

I’m the father of three. All daughters. So far all the grandkids I have are girls. I have become a man well acquainted with all things pink and frilly and sweet. More than once I’ve woken from a nap on the couch to find my toenails painted red. Over the years I’ve grown accustomed to posters of teenaged heartthrobs plastered on bedroom walls and the way girls have of showing their emotions. I’ve learned to appreciate a good rom-com and that it’s all right to cry at the end when the pair lives happily ever after.

Every once in a while somebody asks if I’m disappointed that I never had a boy. Nah, I tell them. I’m pretty content. I like my life as is. I’m used to it.

What I’m not used to, though, is the blazing anger I feel when somebody hurts one of them.

And I’m especially protective of Mindy.

She’s come so far from the tiny girl we met thirty-eight years ago. She’d shaken so hard when they’d put her in my arms. Mindy had felt so light. Lighter than any four-year-old I’d ever known.

But as tiny as she was then, the burden she bore was heavier than any I’ve ever lifted.

It doesn’t seem right that she’s got to go through this too.

Had I known it would end up like this, I might have tried to stop her from marrying Eric. I might have done a better job of protecting her.

Mindy didn’t make it home to eat with us, but at least she sent a text message to let us know as much. Work is keeping her busy these days, which I guess is a good thing. She just got promoted to senior editor over at the local paper—the Bear Run Herald—and our high school football team is having a winning season for the first time since the late 1980s. She’s got plenty to keep her distracted.

Neither Linda nor I hear her Prius roll into the driveway around nine o’clock—those cars are spookily quiet, if you ask me—so when she comes into the family room, she gives me a start.

I may or may not have been halfway into a nice little snooze in my La-Z-Boy.

“I’m sorry,” she says, laughing. “I guess I snuck up on you.”

“It’s all right,” I say.

“Hi, honey,” Linda says. “You want me to warm up some supper for you?”

“Oh, I already ate,” Mindy says. “Thanks, though.”

She drops into the couch cushions, her satchel still strapped across her shoulder. I hit mute to quiet the program Linda and I were watching.

“Everything all right?” Linda asks.

“Yeah.” Mindy nods. “Crazy, but all right.”

She nudges up her glasses with her finger.

“You’re doing a real good job at the paper,” I say. “We’re proud of you.”

“Thanks, Dad.” She pulls her legs up under her.

We three sit and watch the movement on the silent TV for a couple of minutes, and I think about turning the volume on again. But right when I’m about to hit the button, Mindy clears her throat.

“So, I read an interesting article today,” she says.

“One for the Herald?” Linda asks.

“No. Just one I found online,” Mindy answers. “I was doing a Google search and came across it. It’s about this guy who was adopted from Vietnam from the Babylift. Um, like I was.”

“Oh,” Linda says.

“I guess he found this website for people like us who were looking for their family over there.” She licks her lips. Then she cringes. “Not that I’m looking for anybody in Vietnam or anything. You know.”

“Uh-huh.” Linda pulls the lapels of her robe closed around her neck.

“Anyway, somehow he—the guy in the article—got connected with his birth mother and he went to Ho Chi Minh City to meet her.” Mindy lifts her shoulders and smiles. “Isn’t that wild?”

“Yeah,” I say. “After all these years.”

“I know.” Mindy reaches up and scratches the top of her head. “I wouldn’t have thought something like that was possible. But, um, I found that website. It was linked at the bottom of the article. You know how they do that?”

I push the footrest down and lean forward in my seat.

“Did you find anything?” Linda asks.

“Oh no. Not really.” Mindy clears her throat again. “I wasn’t really looking. Just poking around. I . . . I . . .”

“It’s all right if you are looking,” Linda says. “We’ll understand.”

“That’s right,” I add.

“I know.” Mindy bites her bottom lip. “It’s scary to even think about, though.”

From where I’m sitting, I can reach her hand. So I take it in mine, her fingers cold against my warm skin.

“What’s scary about it?” I ask. “Are you afraid you won’t find anything out?”

“No.” She smiles the way she does when she’s holding back emotion. “I’m afraid I will find something or someone. It’s dumb.”

“No it isn’t.”

“I was just curious. That’s all.” She squints her eyes. “I don’t want you to think that you aren’t enough for me.”

Linda leaves her chair so she can sit beside Mindy, putting her arm around her. “We would never think that.”

“You know we’ll support you in whatever you do,” I say. “If you want to look, I say go for it.”

“There’s just so much going on already with work and Eric . . .”

Her hand trembles in mine, and I tell her that everything’s going to be all right. Good even. Maybe not right away, but eventually.

“I probably wouldn’t find out anything anyway,” she whispers.

“But what if you did?” Linda asks.

“I don’t know.” Mindy turns toward Linda. “I guess I’d have to think about taking a trip there. Maybe.”

“By yourself?” I ask.

She’s an adult. I know this in my head. She’s an adult who needs to be free to make her own choices and to take a risk now and then. It’s silly. I know it. Still, worry burrows deep in a man’s heart when he becomes a father, and it’s not so easily coaxed out.

“No. Of course not.” She shakes her head and wrinkles her nose. “Do you think Sonny would let me go without her?”

She’s got a point. She really does.

All Manner of Things

All Manner of Things The Nature of Small Birds

The Nature of Small Birds Paint Chips

Paint Chips My Mother's Chamomile

My Mother's Chamomile A Cup of Dust

A Cup of Dust