- Home

- Susie Finkbeiner

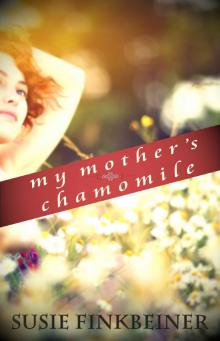

My Mother's Chamomile

My Mother's Chamomile Read online

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this novel are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

MY MOTHER’S CHAMOMILE

Copyright © 2014, Susie Finkbeiner

All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole is strictly forbidden without the express written consent of the publisher.

WhiteFire Publishing

13607 Bedford Rd NE

Cumberland, MD 21502

ISBN: 978-1-939023-36-0 (print)

978-1-939023-37-7 (digital)

In memory of my friend Patt Krauss.

She never told me how to give mercy, she showed me.

Her life was a sprinkling of comfort over others.

To know her was to experience a bit of Christ’s love.

Just a few blinks, Patt, and I’ll see you again.

After she died

it would be years before I realized it.

The dusty aroma that clung to her

scarves, neckline,

her memory,

wasn’t a perfume from the old country

at all

but the breeze

from the back porch

dirt from the garden

crushed up chamomile

steeped with honey.

Don’t be afraid to break up the fragile parts, she told me

once, cupping the hay-colored flowerheads in her left palm

grinding gently with her right fingertips.

That’s what gives the best flavor.

She didn’t believe in magic.

It was miracles

chamomile

God

in that order.

By Elizabeth Sands Wise

“God strengthens and comfort spills. Morning comes.”

~ Jeff Manion

“Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,

the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort,

who comforts us in all our troubles, so that we can comfort

those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves receive from God.”

~ II Corinthians 1:3-4

Contents

Prologue - 1967

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Acknowledgments

Prologue - 1967

Olga

Curly, carrot red hair bobbed up and down among the green and purple, yellow and pink of the garden. Such a small bundle of a girl and every inch bounding with energy. That little thing moved from the moment I said, “Good morning” to the time I scolded, “No more getting out of that bed” at night.

Next to the garden stood a big, brown brick building. Out the open windows, funeral music poured. Quivering tones of the electric organ melted together to form a hymn so full of sorrow, I tried to keep its fingers from working their way into my heart.

Inside the brown brick building, out of my sight, mourning people held down wooden folding chairs. They’d wrap their hands around damp hankies and tissues. When their eyes flicked over to the casket at the very front of the room, a hurt would jab in that place between their lungs. They’d breathe in quick and sharp when the big old rock collected in their throats. No matter how hard they swallowed, the grief wouldn’t go down. That casket cradled the empty body of a person they loved. The mourning filled the space between the walls. No doubt their cries reached all the way through the vents and floorboards and into the apartment my family called home.

It didn’t even take one peek through the window to know what happened in that building. Married to the mortician, I’d seen my share of funerals. More than I would have liked, if I was to be honest.

On funeral days like that one, I had two choices. Either stay inside, cooped up in our apartment and contain my full-of-life four-year-old, listening to the weeping downstairs. Or stand in the sunshine, letting my girl skip and wander and sing to the song of the birds. An easy choice, as far as I was concerned.

That spring, I’d planted my first garden. All I’d put in it were flowers. Every kind that caught my fancy. I never cared too much for growing vegetables. Not after all the years I spent on Uncle Alfred and Aunt Gertie’s farm. No endless rows of soybeans for me. I preferred the dotting of color from a flower garden. And nothing so dainty an exploring child couldn’t tromp through.

My Gretchen loved nothing more than that garden. We’d put in a tire swing hanging on a thick branch of our old oak tree. And my husband Clive had built her a nice sandbox with a wide umbrella for shade. Still, even with all those choices, she wanted to be in with the flowers.

My eyes moved from here to there as she darted all about, up one path and down the next. When she made her way to the very center, she stopped. Turning her head one way and the other, she lifted her little hands, palms down with arms held straight as yard sticks. Like wings. For just a moment, I worried that she intended to fly away from me. A silly thought, I knew it. Most just-for-a-moment worries of mine turned out to be nothing but silly. Still, I couldn’t keep them banished.

Oh, how I fretted over losing her. I’d never had such strong terror in all my life. I’d seen too many tiny caskets in my time living above the funeral home. I prayed, begging to be spared that loss. I didn’t know of a parent who hadn’t prayed that same thing.

Death never made sense at all. No reason. No rhyme. Willy nilly.

Blinking away the fear, I let my eyes focus back on her. My child. The only one I ever got to have. The only baby my body didn’t reject. I fought off the mourning of those little, nameless ones. In those days, we didn’t talk about miscarriages. We didn’t allow the sadness. It just sat in our hearts as secret shame.

“Be thankful for the one we got,” my husband, Clive, would say, rubbing calloused thumbs against my cheeks, pushing away round tears. “If God wants us to have more, He’ll give them to us.”

; I swatted the thoughts and the doubts, shooing them like a sweat-bee. Trying to be thankful for the one I got, I kept my eyes on the carrot red, curly headed girl.

Her tiny fingertips skimmed the tops of tall flowers. Spinning, she hung her head back, the hair brushing the spot between her shoulders. The faster she went round and round, the tighter she held her eyes shut. Fair skinned face covered with ginger colored freckles. Big old baby-toothed smile from ear to ear.

She stopped her spinning. Wobbling, she stood, the world tipping her from side to side. Her giggle was enough to keep me glad my whole life through. Big green eyes looked up at me, crossing each other and blinking hard.

“You get yourself dizzy, Gretchie?” The lavender plant tickled against my ankles as I stepped around it toward my daughter. “You sure were spinning fast.”

When she nodded, those red sausage curls bounced and bumped against her chubby cheeks. Those cheeks begged to be kissed. Never did a day go by without me covering her soft face with smooches a plenty. I had no idea how long she’d abide me loving on her like that. I determined to give all the kisses I could for as long as she’d allow them. Bending down, I smushed my lips into the chub. Putting her hands on either side of my face, she planted a big kiss right on my lips.

“Oh, thank you, sugar plum.”

I didn’t wipe that wet kiss off. I let it dry all of its own in the warm air. That way, I could feel it a little longer. I believed that kisses from my girl were strong evidence of God’s love for me.

“Mama, can you tell me about the flowers?” How her voice squeaked brought joy into my heart. “Please, Mama.”

“I like how you asked so nice.” My fingers smoothed the flyaway strands of her hair.

“What’s the pink one?”

“Well, honey, that’s the tea rose.” I picked the bloom and held it to her nose. “Go on. Give it a whiff. It smells good, doesn’t it?”

She sucked in through her nose so hard the petals stuck to her nostrils. Her giggle again. Oh, the Lord sure knew what He was doing when He designed a little girl’s laugh.

“Did it tickle?” Folding my skirt up under me, I sat on the ground in the middle of a path.

She nodded and rubbed her nose. I pulled her onto my lap, letting her sniff in the aroma of that rose until she’d finished with it. We sat in the garden, letting the sun cover us. Every once in a while, we’d look at each other and smile. So seldom did she sit still like that, I cherished the moments with her nestled in my arms.

She turned sideways. Reaching up one of those hands of hers, she touched my hair. “Your hair is orange.”

“Just like yours,” I said.

“I’m going to be big like you when I’m a mama.” She twisted a strand of my hair around her pointer finger.

“Yes, you are.”

“When am I going to have babies?”

“I don’t know.” My arms forming a circle around her little body felt like the most right thing in all the world. “Probably not for a good long time.”

“Am I going to be pretty like you?”

“You sure are pretty now, Gretchie.” Heat from the sun radiated off her hair as I kissed the top of her head and pulled her tighter to me. “But you know that pretty isn’t what matters, don’t you?”

“I know, Mama.” She rested against me, her head under my chin. “My heart is made of gold.”

“A golden heart, yes,” I said. “That’s what matters.”

“Mama, tell me about the fairy flower.” She yawned, drowsy from the sunshine. “Please.”

Out of the corner of my eye, a lanky chamomile flower danced in the wind. It grew up wild among the other flowers. Tall, green, spindly legs under heads of yellow and white.

“A long time ago, many years before you were even thought of, there was a little girl,” I began.

“Was she like me?” She sat up, turning to look into my face.

“A bit like you.” I stopped to make a sad face. “But, unlike you, she was a very sad little girl.”

Gretchen imitated my expression. Her lips turned down and her eyes went soft. “Why was she sad, Mama?”

“Well, honey, because she lost her mother.”

“Did she try to find her?” Even though she knew the story, she followed the ritual of the telling.

“No. See, her mama got real sick and went to be with Jesus.” My fingers brushed through her soft hair, pushing some of it behind her ears.

“She died?” Gretchen’s little face covered with a frown.

I nodded. “Sometimes that happens. Isn’t it just awful?”

That golden heart of hers showed in the tears which gathered in the corners of her eyes. As many times as I told her the story, she never got dull to it. The telling always broke her precious heart.

“Then what happened?” Her eyes grew large. “Something good happened, didn’t it?”

“Not yet,” I whispered before going on. “Well, the girl was very lonely. You see, she had to leave her home and go live with her aunt and uncle and all her boy cousins.”

“What about her daddy?”

“Oh, he wasn’t ready to care for her all by himself. He didn’t even know how to make piggy tails in her hair. He couldn’t raise her right.” A bird darted, a flash of red, over our heads. We both paused in our story to watch it pass.

“Go on, Mama.”

“Well, her aunt and uncle had a farm. She had an awful hard time getting to sleep. See, she’d lived in the city all her life. A farm has all kinds of different smells and sounds. And it got real dark at night.”

“Did she get scared?”

“Oh, did she ever.” My fingers twisted the chamomile, snapping it loose and letting it fall into my palm. “But she remembered her mother making tea that helped her sleep. She used flowers to make it.”

“Like that one?” She took the chamomile from me.

“Just like that one.” I found a few other flowers, picking them and adding them to my hand. “The girl found some of them in her aunt’s garden. Can you tell me the colors?”

“Purple, pink, and green.” She pointed to each one.

“Very good, honey. You’re doing real good with your colors.”

She sat up straight and grinned, proud as could be.

“Now,” I continued. “This one here, the one with the white petals and the yellow middle, that one’s chamomile.”

“The fairy flower,” she said, her voice a whisper full of awe.

“That’s right. And its friends lavender and tea rose and mint.” I folded her hand over the flowers. “The girl gathered a little of each of them.”

“Did she make some tea?” Sly smile crinkled into the corners of her eyes.

“Pretty soon, you’re going to tell this story better than me.” I winked at her. “The girl did make some tea from the flowers. A smooth, magic tea. Just a tiny bit sweet. The tea helped her rest.”

“Did it make her happy?” She touched the flowers, poking at them with her fingertips.

“No, honey. Tea can’t make anybody happy. Even if it is made from fairy flowers. Not a tea in the whole wide world has that kind of magic.” A ringlet of her hair fluttered in the breeze. “But it did help her feel a little peaceful. And quiet.”

“What happened next?” Chubby cheeks rose, making room for a wide smile. “She got happy again?”

“She sure did get happy.” I stood, putting my hands under her arms and lifting her up. “But not because of the tea. She got a bundle of joy out of life.”

“How?” She nuzzled her face into my neck.

“God let her be loved.” Pushing my nose into her hair, I breathed her in. She smelled like sunshine itself. “Are you hungry, Gretchen?”

She nodded. “May I please have a peanut butter and banana sandwich?”

“Oh, those sweet manners. I’d love to make you a sandwich.” I carried her to the house. “Now, Daddy’s not done yet. They should be through real soon, though.”

“Will Daddy c

ome upstairs for lunch?”

“Not right away. They have to go over to the cemetery first.” I pulled the door open to the back way into our apartment. “Remember, we must be hushed until they all leave, okay?”

She nodded her little head again.

I carried her, climbing the stairs, thankful for the way in and out that didn’t take us through the mourners. I hated the thought of my little girl, so full of life, seeing something so empty of it. Not that young, at least.

“Mama,” she whispered, her mouth so close to my ear, I felt her moist breath. “What’s the little girl’s name? The girl who drank the fairy tea?”

“Hush, honey.” I pushed her head against my shoulder as I took the last few steps.

“But who is she?”

“How about I get your crayons out?” I asked. “You can color a picture of the flowers while I make your sandwich. I bet Daddy would love to see it when he’s done with work.”

“Okay,” she said against my cheek.

Her little hand dangled over the back of my shoulder, clinging to the chamomile as tight as her fingers could.

Chapter One

Present Day

Evelyn

The widow sat in front of the casket. Her wide backside filled the seat of a metal folding chair, overflowing it by an inch or so. I wished we could have found something more comfortable for her. Something with a little more padding. She didn’t seem to mind so much, though. Her big, corn-fed sons sat on either side of her, both with an arm around her shoulders.

Sunshine blazed on the mourners. They pulled at tight collars and wiped trickles of sweat from foreheads and napes of necks. A glaring gleam reflected off the shiny, gray casket that hung, suspended by thick straps, over an open hole in the ground. Flowers draped across the closed lid, wilting in the heat. Red, white, and blue carnations with an American flag ribbon running through the blooms.

My brother Cal and I ushered the people under the canopy, hoping to keep them out of the sun. Silently, they followed our direction, uncomfortable in the tight space. Thick, humid August air hung from the sky, unmoving.

All Manner of Things

All Manner of Things The Nature of Small Birds

The Nature of Small Birds Paint Chips

Paint Chips My Mother's Chamomile

My Mother's Chamomile A Cup of Dust

A Cup of Dust