- Home

- Susie Finkbeiner

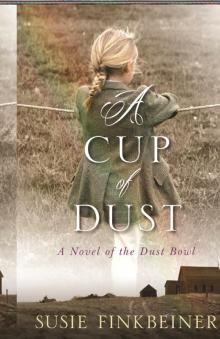

A Cup of Dust

A Cup of Dust Read online

“Born in Oklahoma November 12, 1931, I lived through the decade known as the ‘Dirty Thirties.’ A time when farmers in the Wheat Belt broke up far too much prairie sod and planted wheat to cash in on the government’s price support program. This led to soil erosion and the most difficult times captured in the compelling novel A Cup of Dust. The author does a great job of giving the reader a feel for those dark days in our nation’s history. Very intriguing reading!”

—Virgil Dwain McNeil, a Dust Bowl survivor

“I have just finished reading Susie Finkbeiner’s A Cup of Dust. The story is excellent and an accurate story of the dust storms. I lived thru it in southeastern Nebraska and it would get so dark, the chickens would go to roost at 3 pm. My Dad had to go to Iowa to get hay to feed our cows. There was none available to buy in Nebraska.”

—Phyllis M. Wagner, Lincoln, Nebraska

“Riveting. An achingly beautiful tale told with a singularly fresh and original voice. This sepia-toned story swept me into the Dust Bowl and brought me face-to-face with both haunting trials and the resilient people who overcame them. Absolutely mesmerizing. Susie Finkbeiner is an author to watch!”

—Jocelyn Green, award-winning author of the Heroines Behind the Lines Civil War series

“Without a doubt Finkbeiner’s best work to date, A Cup of Dust is simultaneously intimate and epic. The compelling voice of young Pearl describes a world of biblical-proportion plagues unleashed on the Oklahoma Panhandle in a way that is both grounding and disturbing—with the plague of frogs replaced by jackrabbits, boils by pneumonia, locusts by unyielding walls of sky-blackening dust, and the growing sense that there may not be a God who hears their cries for deliverance very much unaltered.

“At every turn gritty and historically accurate, A Cup of Dust allows us to weather the dust storm of a few months in the hope-and-rain-deprived Great Plains of the 1930s. As I tore through the often sobering text, I found the back of the storm to bring insight, deep empathy, and an enduring sense of redemptive hope.”

—Zachary Bartels, author of The Last Con and Playing Saint

A Cup of Dust: A Novel of the Dust Bowl

© 2015 by Susie Finkbeiner

Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel, Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505.

Published in association with the literary agency of Credo Communications, LLC, Grand Rapids, Michigan

www.Credocommunications.net.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in reviews.

Distribution of digital editions of this book in any format via the Internet or any other means without the publisher’s written permission or by license agreement is a violation of copyright law and is subject to substantial fines and penalties. Thank you for supporting the author’s rights by purchasing only authorized editions.

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

Poem by John Blase on page 10 used by permission.

The persons and events portrayed in this work are the creations of the author, and any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

ISBN 978-0-8254-4388-6

Printed in the United States of America

15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 / 5 4 3 2 1

For Jeff.

I love you.

Thank you for loving me.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I could never live the life of a reclusive author. I’m far too flighty and neurotic. In order to be the best writer I can be, I need people. I just so happen to have some pretty amazing people who prop me up, challenge me, and encourage me. I’d like to tell you about a few of these folks.

Ann Byle is the best agent a girl like me could hope for. She believes in me when I don’t know if I’ve got what it takes. She doesn’t let me whine too much and she tells it like it is. I’d trust her with my life. More than that, I’d trust her with my kids. That’s saying a lot.

Jocelyn Green, Tracy Groot, and Julie Cantrell are authors who have influenced my writing of A Cup of Dust. I learned how to write historical fiction by reading their novels and learned about life by being around them. They are good mentors and even better friends.

Amelia Rhodes became my friend just before we both plunged headfirst into the publishing world. She answers her phone when I call, knowing full well that I might be a hot mess with a brain full of doubts about teeter-tottering self-confidence. She talks me off the ledge, gives me a pep talk, and reminds me of how far God has brought both of us in our five-year-old friendship.

Pam Strickland is the giver of hugs and smiles and overflowing encouragement. She’s quick to listen and even faster to pray. She knows how she helped this novel come to be and she wouldn’t like me bragging about it. Just know she’s part of the reason you have it in your hands.

The team at Kregel has made me feel welcome from the very moment I signed my name on the contract. They have taken my small efforts and collaborated to make Pearl’s story come to life.

A good portion of this book was written at a table at my local Starbucks. That place has become my own personal Cheers because of how great the baristas are. They kept me caffeinated and smiling during the rougher days of writing. Marcia, Catrina, Hananiah, Jaimee, Jeff, Kasey, Lydia, Melissa, Sam, Shawn, Stephanie, and Travis aren’t just great at making a cup of coffee, they’ve become sweet friends and I’m thankful for them.

I wouldn’t be who I am without the love of my Father, the Author of all life. He is the same yesterday, today, and forever, and in that sameness is His unfailing love for His children. He sees us in our weakness, in our vulnerability, in our failings. He doesn’t reject us. Instead, He scoops us up and brings us into His family. I can think of nothing more powerful, more beautiful. Pearl’s story is mine. Yours. Ours. It is the story of God’s great love for His people. He is the one who saves.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Part of the writer’s task is to find and utilize the exactly right word. For the writer of historical fiction, the job is to match word choice to the commonly used vocabulary of the era. In all honesty, some words that were often used in the 1930s are now considered hurtful, abrasive, and racist.

When writing this novel I had to make difficult choices when it came to terms used as identifiers for people of various races. Writing words such as Negro, Injun, and colored made me uncomfortable. However, in keeping with the times, I felt they were consistent.

Since the founding of our nation, race has been a sensitive issue. We look back at the horrors of slavery, civil rights abuses, and the unjust way in which the American Indians were driven from the land. As we experience the racial tensions of our own time, we do well to remember the consequences of dehumanizing others based on the color of their skin. And as we hope for a peaceful future, we can grapple with our various backgrounds and appearances and find that we have a shared heritage that no title can fracture.

“He picked you out,

He picked you up,

He brought you home.”

—Jeff Manion

YOU’RE MY GIRL by John Blase

In that second I first held you

I sensed you as fragile.

Not like a demitasse that if

dropped would break

but like the peach that will

bruise if not carefully kept.

So that is what I’ve tried to do,

to permit only the irritants necessary

for you to shine.

You must know, my girl, that this

has been and

is my happiness.

For you are the best thing that has

ever come into my life.

CHAPTER PAST

Red River, Oklahoma

September 1934

As soon as I was off the porch and out of Mama’s sight, I pushed the scuffed-up, hole-in-the-soles Mary Janes off my feet. They hurt like the dickens, bending and cramping my toes and rubbing blisters on my heels. Half the dirt in Oklahoma sifted in when I wore those shoes, tickling my skin through thin socks before shaking back out. When I was nine they had fit just fine, those shoes. But once I turned ten they’d gotten tight all the sudden. I hadn’t told Mama, though. She would have dipped into the pennies and nickels she kept in an old canning jar on the bottom of her china cabinet. She would have counted just enough to buy a new pair of shoes from Mr. Smalley’s grocery store.

I didn’t want her taking from that money. That was for a rainy day, and we hadn’t had anything even close to a rainy day in about forever.

Red River was on the wrong side of No Man’s Land in the Panhandle. The skinny part of Oklahoma, I liked to say. If I spit in just the right direction, I could hit New Mexico. If I turned just a little, I’d get Colorado. And if I spit to the south, I’d hit Texas. But ladies didn’t spit. Not ever. That’s what Mama always said.

I leaned my hip against the lattice on the bottom of our porch. Rolling off my socks, I kept one eye on the front door just in case Mama stepped out. She was never one for whupping like some mothers were, but she had a look that could turn my blood cold. And that look usually had a come-to-Jesus meeting that followed close behind it.

She didn’t come out of the house, though, so I shoved the socks into my shoes and pushed them under the porch.

Bare feet slapping against hard-as-rock ground felt like freedom. Careless, rebellious freedom. The way I imagined an Indian girl would feel racing around tepees in the days before Red River got piled up with houses and ranches and wheat. The way things were before people with white faces and bright eyes moved on the land.

I was about as white faced and bright eyed as it got. My hair was the kind of blond that looked more white than yellow. Still, I pretended my pale braids were ink black and that my skin was dark as a berry, darkened by the sun.

Pretending to be an Indian princess, I ran, feeling the open country’s welcome.

If Mama had been watching, she would have told me to slow down and put my shoes back on. She surely would have gasped and shook her head if she knew I was playing Indian. Sheriff’s daughters were to be ladylike, not running wild as a savage.

Mama didn’t understand make-believe, I reckoned. As far as I knew she thought imagination was only for girls smaller than me. “I would’ve thought you’d be grown out of it by now,” she’d say.

I hadn’t grown out of my daydreams, and I didn’t reckon I would. So I just kept right on galloping, pretending I rode bareback on a painted pony like the one I’d seen in one of Daddy’s books.

Meemaw asked me many-a-time why I didn’t play like I was some girl from the Bible like Esther or Ruth. If they’d had a bundle of arrows and a strong bow I would have been more inclined to put on Mama’s old robe and play Bible times.

I slowed my trot a bit when I got to the main street. A couple ladies stood on the sidewalk, talking about something or another and waving their hands around. I thought they looked like a couple birds, chirping at each other. The two of them noticed me and smiled, nodding their heads.

“How do, Pearl?” one of them asked.

“Hello, ma’am,” I answered and moved right along.

Across the street, I spied Millard Young sitting on the courthouse steps, his pipe hanging out of his mouth. He’d been the mayor of Red River since before Daddy was born. I didn’t know his age, exactly, but he must have been real old, as many wrinkles as he had all over his face and the white hair on his head. He waved me over and smiled, that pipe still between his lips. I galloped to him, knowing that if I said hello he’d give me a candy.

Even Indian princesses could enjoy a little something sweet every now and again.

With times as hard as they were for folks, Millard always made sure he had something to give the kids in town. Mama had told me he didn’t have any grandchildren of his own, which I thought was sad. He would have made a real good grandpa. I would have asked him to be mine but didn’t know if that would make him feel put upon. Mama was always getting after me for putting upon folks.

“Out for a trot?” he asked as soon as I got closer to the bottom of the stairs.

“Yes, sir.” I climbed up a couple of the steps to get the candy he offered. It was one of those small pink ones that tasted a little like mint-flavored medicine. I popped it in my mouth and let it sit there, melting little by little. “Thank you.”

He winked and took the pipe back out of his lips. It wasn’t lit. I wondered why he had it if he wasn’t puffing tobacco in and out of it.

“Looking for your sister?” His lips hardly moved when he talked. It made me wonder what his teeth looked like. I’d known him my whole life and couldn’t think of one time that I’d seen his teeth. “Seen her about half hour ago, headed that-a-way.” He nodded out toward the sharecroppers’ cabins.

“Thank you,” I said with a smile.

“Hope you catch her soon,” he said, wrinkling his forehead even more. “Her wandering off like that makes me real nervous.”

“I’ll find her. I always do,” I called over my shoulder, picking up my gallop. “Thanks for the candy.”

“That’s all right.” He nodded at me. “Watch where you’re going.”

I turned and headed toward the cabins, hoping to find my sister there but figuring she’d wandered farther out than that.

My sister was born Violet Jean Spence, but nobody called her that. We all just called her Beanie and nobody could remember why exactly. Daddy had told me that Beanie was born blue and not able to catch a breath. He’d said he had never prayed so hard for a baby to start crying. Finally, when she did cry and catch a breath, she turned from blue to bright pink. Violet Jean. The baby born blue as her name. Just thinking on it gave me the heebie-jeebies.

When I needed to find Beanie, I knew to check the old ranch not too far outside town. My sister loved going out there, being under the wide-open sky. I was sure that if a duster hit, God would know to look for her at that ranch, too. Meemaw had told me that God could see us no matter where we went, even through all the dust. I really hoped that was true for Beanie’s sake.

Meemaw had told me more than once that God saved us from the dust. So I figured He was sure to see me even if Pastor said the dust was God being mad at us all.

In the flat pasture, cattle lowed, pushing their noses into the dust, searching out the green they weren’t like to find. I expected I’d find Beanie standing at the fence-line, hands behind her back so as to remember not to touch the wire. Usually she’d be there looking off over the field, eyes glazed over, not putting her focus on anything in particular.

Daddy said she acted so odd because of the way she was born. She could see and hear everything around her. But when it came to understanding, that was a different thing altogether.

I found Beanie at the ranch, all right. But instead of looking out at the pasture, she was sitting in the dirt, her dress pulled all the way up to her waist, showing off her underthings in a way Mama would never have approved of. Mama would have rushed over and told Beanie to put her knees together, keep her skirt down, and sit like a lady. I didn’t think my sister knew what any of that meant.

Being a lady was just one item on the laundry list of things my sister couldn’t figure out. I wondered how much that grieved Mama.

Mama had told me Beanie was slow. Daddy called her simple. Folks around town said she was an idiot. I’d gotten in more than one fight over a kid calling my sister a name like that. Meemaw had said those folks didn’t understand and that people sometimes got mean over what they didn’t understand.

“I

t ain’t no use fighting them,” she had told me. “One of these days they’ll figure out that we’ve got a miracle walking around among us.”

Our own miracle, sitting on the ground grunting and groaning and playing in dirt.

“Beanie.” I bent at the waist once I got up next to her. My braids swung over my shoulders. “We gotta go home.”

The tip of Beanie’s nose stayed pointed at the space between her spread out legs. Somehow she’d gotten herself a tin cup. Its white-and-blue enamel was chipped all the way around, and I figured it was old. She found things like that in the empty houses around town. Goodness knew there were plenty of abandoned places for her to explore around Red River. Half the houses in Oklahoma stood empty. Everybody had took up and moved west, leaving busted-up treasures for Beanie to find.

She’d hide them from Mama under our bed or in our closet. Old, tattered scraps of cloth, a busted up hat, a bent spoon. Everything she found was a treasure to her. To the rest of us, it was nothing but more junk she’d hide away.

“You hear me?” I asked, tapping her shoulder. “We gotta go.”

She kept on digging in the dirt with that old cup like it was a shovel. Once she got it to overflowing, she held it in front of her face and tipped it, pouring it out. The grains of sand caught in the air, blowing into her face. I stood upright, pulling the collar of my dress over my face to block out the dust. She just didn’t care—she let it get in her mouth and nose and eyes.

“That’s not good for you,” I said. “Don’t do that anymore.”

Little noises came out her mouth from deep inside her. Nothing anybody would have understood, though. Mostly it was nothing more than short grunts and groans. Meemaw liked to think the angels in heaven spoke that same, hard tongue just for Beanie. Far as I knew it was nothing but nonsense. Beanie was sixteen years old and making noises like a two-year-old. She could talk as well as anybody else, she just didn’t want to most of the time.

All Manner of Things

All Manner of Things The Nature of Small Birds

The Nature of Small Birds Paint Chips

Paint Chips My Mother's Chamomile

My Mother's Chamomile A Cup of Dust

A Cup of Dust